COV19 EDIT: Because of the pandemic, Git is now nothing like taking a flight or being at an airport.

Git is an open-source technology that keeps records of your changes. It allows for collaborative development. It allows you to know what changes you made and when, and sometimes to revert changes you made. It can go even further than that though, and even be embedded within your team as a process to continuously integrate and deploy changes in code to another target location (a server, an application for example.)

So how does it work?

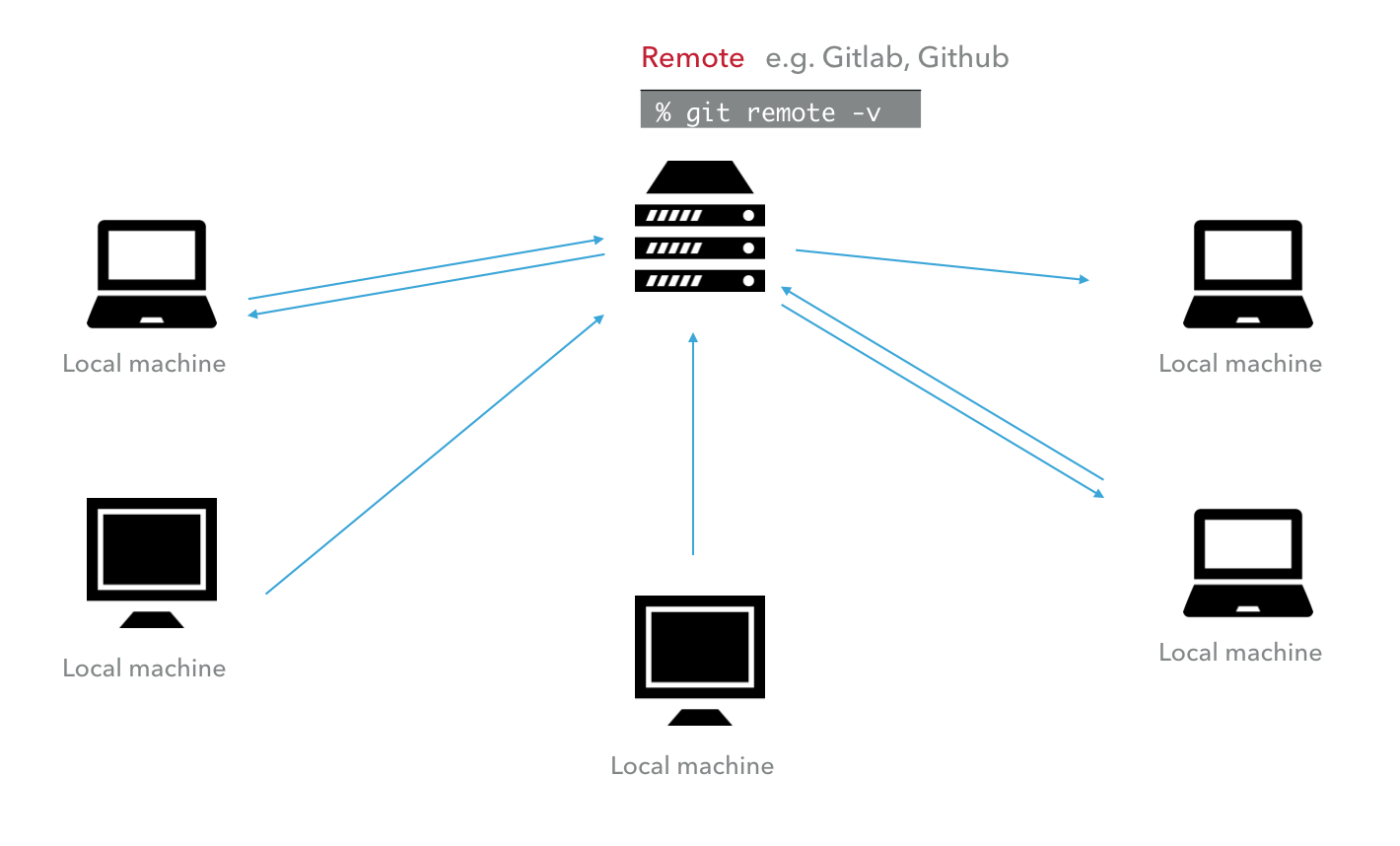

Its quite simple conceptually - you have local machines you and other each work on, and everyone stores and retrieves their work through revision control - by ‘committing’, ‘pushing’ and ‘pulling’ work.

A good starting point for tutorials is here

How does your day-to-day workflow change?

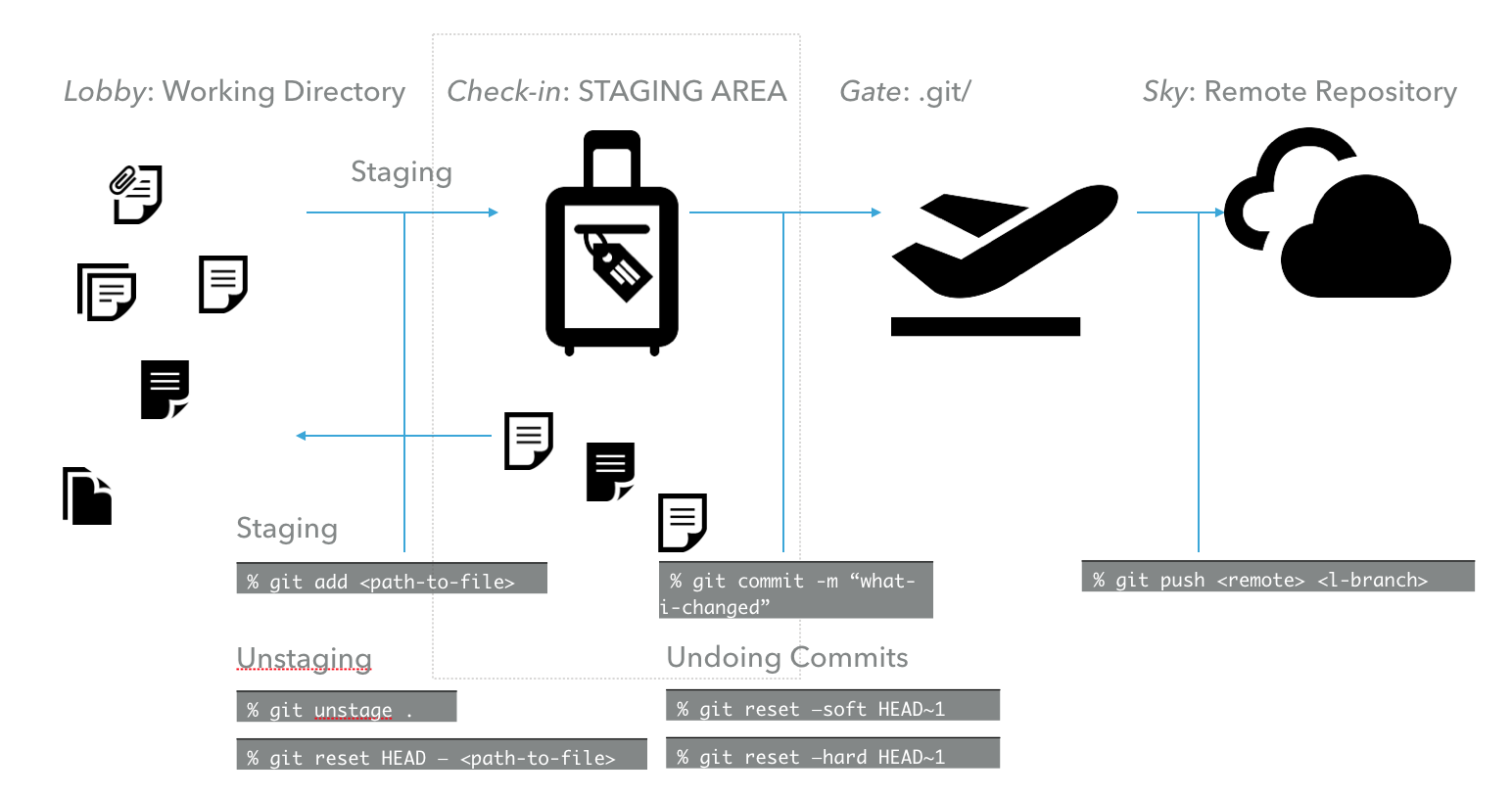

If you’re a frequent flyer, then git should be pretty easy to grasp - because it’s not too dissimilar to the hassle of an airport. Forget all the time wasting you do in an airport because once you grasp git, it only takes a few commands to get going. The golden rule is though - keep. git. simple.

Specific, Advanced Usage of Git

- Can automate your documentation, building, testing and compilation through continuous integration

- Can help collect your deployment through containerisation (i.e. Docker)

- Can be used in conjunction with Jekyll and Github pages, to produce static websites and blogs

- Create efficient, productive workflow for small or large teams

Starting a new repo can be quite tricky sometimes, and there are a number of ways you can get yourself into a mess. I’ll try to explain what I can about how it works, and how you can dig yourself out.

Manually creating one

For the source tutorial on Github, go here. On Gitlab, go here.

Probably the most common way of starting off with Git is to create a repository online, and then do an initial commit and push inside your local area.

Create a new repository on GitHub. To avoid errors, do not initialize the new repository with README, license, or gitignore files. You can add these files after your project has been pushed to GitHub.

Open Terminal.

Change the current working directory to your local project.

Initialize the local directory as a Git repository.

1

% git init

- Add the files in your new local repository. This stages them for the first commit.

1

2

% git add .

# Adds the files in the local repository and stages them for commit. To unstage a file, use 'git reset HEAD YOUR-FILE'.

- Commit the files that you’ve staged in your local repository.

1

2

% git commit -m "First commit"

# Commits the tracked changes and prepares them to be pushed to a remote repository. To remove this commit and modify the file, use 'git reset --soft HEAD~1' and commit and add the file again.

At the top of your GitHub/Gitlab repository’s Quick Setup page, click to copy the remote repository URL.

In Terminal, add the URL for the remote repository where your local repository will be pushed.

1

2

3

4

% git remote add origin <remote repository URL>

# Sets the new remote

% git remote -v

# Verifies the new remote URL

- Push the changes in your local repository to GitHub/Gitlab

1

2

git push -u origin master

# Pushes the changes in your local repository up to the remote repository you specified as the origin

You will also see this around, too , which does the same.

1

git push --set-upstream origin master

Push to create a project

Introduced in Gitlab 10.5

This is actually a way neater way of creating a project locally and pushing it without leaving your terminal, and doesn’t require you to create a project locally and remotely, and sync them.

You can just do either

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

## Git push using SSH

% git push --set-upstream git@gitlab.example.com:uname/nonexistent-project.git master

% git push --set-upstream git@gitlab.eps.surrey.ac.uk:wm0014/my-poem-for-cvssp.git master

## Git push using HTTP

% git push --set-upstream https://gitlab.example.com/namespace/nonexistent-project.git master

At this point, you can now drink beer

The HEAD in Git

The HEAD is a reference to the last commit in the currently checked-out branch.

You can think of the HEAD as the “current branch”. When you switch branches with git checkout, the HEAD revision changes to point to the tip of the new branch.

You can actually see what the head is doing in your local repo by running cat .git/HEAD, which will output the refs/heads/master. It is possible for HEAD to refer to a specific revision that is not associated with a branch name. This situation is called a detached HEAD.

1

2

3

4

» ~/Development/Poem-for-Git/Poem-for-Git git branch -a

* master

remotes/origin/HEAD -> origin/master

remotes/origin/master

1

git remote add origin <myproject.git>

You can prove this has been added by doing git remote -v and removing it by doing git remote rm origin. You can rename the remote to anything you want - like:

1

git remote rename origin banana

git push --set-upstream

sets the default remote branch for the current local branch.

One way to avoid having to explicitly do –set-upstream is to use the shorthand flag -u along-with the very first git push as follows

git push -u origin name/of/what/to/push

Any future git pull command (with the current local branch checked-out), will attempt to bring in commits from the

Initial Steps:

- Creating a new Repository

- Cloning an existing Repository

- You start a new repo inside the repository you want with the

git initcommand. - Write some code

- Type

git addto add the files *

List all branches with git branch -a

When checking out in git, there are two options.

Create and track a local branch in your working tree by running git branch <branch>, and then running a git checkout <branch>. Another way to do this in one command is to add the -b option in git checkout -b <feature-branch/new-feature>

I can push this with git push origin <branch>

what is -u?

Another similar situation however, is what if another user or developer had created a branch and you wanted to track and modify this ?

You would first run git fetch, similar to git pull, but git pull is only related to branches that you currently track.

This will update files in the working tree to match the version in the index or the specified tree. Git checkout will also update the HEAD too.

When it comes to merging, you must checkout to the branch you want to merge to. Remember to commit the change first. You can also do this without adding, by doing git commit -am "type some funky message here"

Sometimes the nature of our work and our branch changes, so we need to make sure we are making everyone else informed of that too. We can rename our branch using git branch -m <name_of_branch> <renamed_this_whatever>

We can actually see the difference between our branches by doing calling git diff

a cool command you might not know about is git diff <name_of_branch>..<branch_to_compare>

The best gitflow procedure I thought made the most sense was from this website:

https://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model/?

The specifies

The different types of branches we may use are:

Feature branches Release branches Hotfix branches

When starting work on a new feature, branch off from the develop branch.

1

2

3

$ git checkout -b myfeature develop

Switched to a new branch "myfeature"

Incorporating a finished feature on develop

Merging in git can be scary. But there are some things I wish I knew before I started to merge. First. What branch should I be on to merge into what? Imagine you are on a motorway for a second. You want to be in the lane (or branch)

If you are the lorry driver in Italy, the annoying car merging into your lane right in front of you is the thing that is affecting you. Therefore,

git checkout my-lane git merge car-merges-into-lane

This will perform a merge from the car-merging into your lane into the branch you are driving on - your god dam lane. Again, it is a little weird to think in this reverse way, and for ages I thought it was the other way around, I would be checked out on a branch and merge into another using the branch I was on. A bit weird, I know.

For something more elaborate, like within a Gitflow model, more sensible names for branches help finished features that may be merged into the develop branch to definitely add them to the upcoming release. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

$ git merge --no-ff myfeature

Updating ea1b82a..05e9557

(Summary of changes)

$ git branch -d myfeature

Deleted branch myfeature (was 05e9557).

$ git push origin develop

The –no-ff flag causes the merge to always create a new commit object, even if the merge could be performed with a fast-forward. This avoids losing information about the historical existence of a feature branch and groups together all commits that together added the feature.

Some Get Out Jail Free Commands in Git

- Please be aware of these commands

Don’t go throwing them around, you can do some

- You can checkout specific files using

git checkout -commit#id --path-to-file git revertgit reset --hard HEAD